Compiled and researched by Resoum Kidane

Following the crackdown on the reformist movement, the government introduced the Warsai Yikaalo Development Campaign (WYDC) in 2012. Through this campaign, the national service was extended indefinitely enabling the government to avoid mass demobilization following the ceasefire in the 2000 border war.

Additionally, in 2003, the government announced a shift from a system of highly selective promotion in Senior Secondary School (9-12) to a system of mass promotion. Thereafter the Ministry of Education declared that the education system would be expanded from grade 11 to grade 12, but all grade 12 students from the whole country would have to attend school in one boarding facility located in Sawa, the national military training center [Riggan, 2016, page 7)-

To most Eritreans, the mention of going to Sawa evokes fear and anxiety and is emblematic of the hardships, and coerciveness, of military training. The phrase”in Sawa” merges references to an actual place that has negative connotations associated with the hardships of military training with negative sentiments about service more generally. (Riggan, 2016 page 67)

Testimony of Bisrat Habte Micael who was born in 1981.

"The time in Sawa was hard. It was the rainy season and the facilities at Sawa were poor at that time.Many became ill, and got hepatitis. Especially women frequently got a hiccup, we call this lewti. Even when ill we were forced to take part in the roll-call. Only when you were very seriously ill was it possible to get a postponement from National Service.

We were forced to take part in military exercises until we were completely exhausted. They did not care whether you would die or not.” She also mentioned that many girls were raped. There were girls who adapted themselves to the situation and made advances to officers out of their own initiative. Those who didn't comply, who rejected the men were given the worst work or sent into the war readmore

Dr David Binozzini in his presentation which he gave at the Federal Office for Migration on the 26th Feb., 2012 said that women were afraid of going to Sawa, because of the high risk of being raped readmore

The 2015 UN Commission of inquiry on Eritrea (COI) also finds that women are at a disproportionate risk of discrimination and violence within the military training camps and are targeted for sexual abuse on account of their gender. The Commission considers the overall circumstances of the military training centres to be situations of control in which conscripts, particularly women and girls, are denied their rights creating a vulnerability to violence. The Commission is of the view that in addition to women and girls being targeted to perform domestic labour in officials’ quarters which constitutes an additional deprivation of their liberty, they are also targeted for sexual abuse by officials.

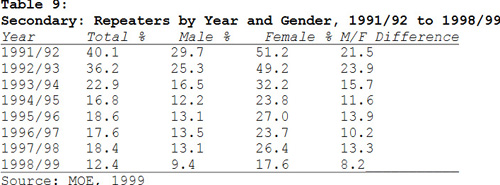

The table below indicates the high number of females repeating school years between 1991/92 and 1998/99. The number of female repetition also exacerbate after 2002 as a way to avoid the hardships of military training in Sawa. Since 2002, Eritrea has a serious problem with a high dropout rate among female students from secondary schools so as to avoid going to Sawa.

According to Rena (2007) only about 3 per cent of the youth in the 17-23 age groups get an opportunity for higher education and transfer to the new technical college in Mai Nefi . The enrolment rates in science, medicine, engineering and technology, business and economics and arts and social sciences vary from time to time.

Other students who failed are immediately transferred to the Army and spend the most productive years of their life in uncertainty. 10,000 school leavers are sent every year to the army and restricted to road construction, dam and house building as part of their military service. Those conscripts are not only restricted to slave labour but they also become a victims of human rights abuse by the EPFDJ. Tronvoll (2014, 113) states whenever they conduct a meeting or a course of instruction, the commanding officers expect opinions and reactions from the soldiers. Whenever a person speaks out against the government leadership, or questions policy or strategy, no immediate action will necessarily be taken but later, at night, they will come and pick them away for torture and detention. Many soldiers disappear in this during the night.

Generally the poor educational system during the Derg regime and the proclamation of National Service in 1994 have to some extent contributed to the widening gender gap in higher education and poor students achievement in post-liberation.

Initially the Eritrean government gave hope to young people that after completing their national service they will have an opportunity to gain employment. This turned out to be untrue. Regarding this Lula in her testimony published in ‘Violence against women’ 27th of November 2013, stated: “The government’s propaganda promises jobs to the youth on completing the obligatory military service. But they prevent us from studying and by doing so they steal from us the capacity to have and realize our dreams”.

Subsequent to this spontaneous uprising, around 10, 000 fighters who joined the EPLF in 1990 were demobilised, to return to civilian life out of fearing that similar protests might occur. During that year the Eritrea Provisional Government also sent several young people including these demobilized fighters to Arab countries to work as maids in Arab households or in the construction industry.

The picture below shows that a gathering of the young people for registering and processing was recorded at the Labour Office Asmara in 1993 [but it is no longer available on YouTube.]

Consequently, many young women who completed their National Service Programme either migrated to the Arab countries to work as maids or got married. Regarding this Rahel in her interview with Muller briefly mentioned what happened to her sister after completing the National Service in 1994.

Rahel's sister did three years of National Service, first at the referendum on Eritrea's independence, then with the Ministry of Labour and Human Welfare, and then in 1994 she was among the first round who went to Sawa for obligatory military service. After she returned from that service, there was no work in Eritrea and when she saw a job advertised in Lebanon as a housemaid she decided to go there and earn some money. To this day she is still working there. She does not like it and plans sometime in the future to shift to another country where she eventually can continue her education.

According to Rahel, her sister was good at education, she was studying, she was trying to join the Asmara University but when she was in her eleventh grade, there was the revolution with the EPLF was coming towards Asmara in 1991... [ source from the making of elit women by Muller, Tanja R 2005. 97]

Rahel in her interview with Muller also states that when she grew up one of her older sisters was a role model for her. Rahel would sit with her whenever she studied and her sister was very intelligent and good at education... Like Rahel's sister there are many young people keen to study and intelligent but have their futures blighted by the National Service Programme and forced military drafting.

[Back to the Table of contents]------ [NEXT PAGE]

ehrea.org © 2004-2017. Contact: rkidane@talk21.com | ||||